Date: Thursday, May 15, 2025

Written by Inspector Conor King, this article first appeared in a special issue of RILO Western Europe Info Magazine in May, 2025.

"Hey Sergeant, something is knocking people on their butts." This simple description of the effects of fentanyl was the very first time I heard about this drug emerging in Western Canada.

It was the Autumn of 2013. I was the Sergeant in charge of a team of police officers who walked the beat in downtown Victoria, a city of 350,000 and the capital of the Province of British Columbia.

Situated on Canada's rugged Pacific coast, Victoria is a picturesque city, but it does have some rougher neighborhoods, where tents dot grassy boulevards near crowded homeless shelters and where drug dealers sell cocaine, meth and heroin to people who slip away into nearby alleys. Before 2013, no one in these neighborhoods sold or used fentanyl. This powerful pain medication was highly restricted and unavailable outside of a medical application.

All that changed in just a few months, though it took decades to set the stage for the rise of fentanyl.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, the United States was the largest per capita consumer of prescription opioids in the world. Canada came in second. Opioids, synthetic versions of morphine, had for years been reserved for the most serious of ailments, like cancer-related pain and post-operative recovery. However, seeing an opportunity to expand corporate profits, pharmaceutical companies aggressively marketed these opioids for ailments previously deemed unsuitable, like chronic back pain, which is notoriously hard to treat and persists for years. Patients sought relief by using more pills for more extended periods. Unsurprisingly, addiction to these opioids reached epidemic levels.

Chief among the drugs of abuse was Purdue Pharma's OxyContin 80 mg, which delivered a slow, sustained release of oxycodone. They sold in Canada as round green tablets. Dealers called them greenies and they packed a punch. Greenies could be crushed and snorted or injected; for many people, they were as good as, or better than, heroin. Thousands of people became addicted; some used greenies and heroin interchangeably, depending on what they could access.

But as addiction levels continued to climb, in 2012, the Government of Canada prohibited the sale of OxyContin 80mg, and pharmacists pulled it from their shelves.

This created a vacuum and an opportunity that organized crime groups were keen to exploit, and they knew a perfect way; supply the illicit market with greenies once again - though these pills would contain fentanyl instead of oxycodone. Canadian crime groups with transnational connections in China knew that fentanyl was unregulated there, was potent in small amounts, and was easily produced in the countries’ thousands of chemical factories.

Using freight forwarding companies like FedEx and UPS, crime groups shipped fentanyl by air from China to hub cities like Vancouver and Calgary. There, they used pill press machines, industrial green dye, counterfeit "OxyContin" stamps and fentanyl to produce imitation OxyContin tablets. These pills hit the street so fast that many users didn't notice the switch from real to counterfeit. They didn't know they were taking highly toxic fentanyl or that each pill could have a different dose because the criminals behind their production had no regard for safety or consistency in their illegal warehouse labs.

"Something is knocking people on their butts," the officer said to me in 2013 after he'd heard from street nurses that a powerful drug was circulating in the illicit opioid market. That turned out to be a significant understatement.

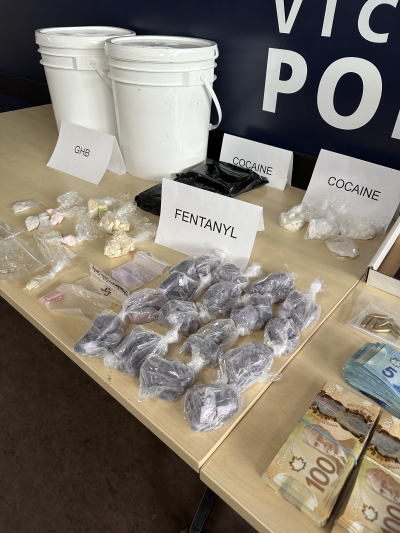

In the weeks that followed, undercover officers purchased these pills and we detected fentanyl at staggering levels. While medical-grade fentanyl sold at a maximum dose of .8 mg, the counterfeit pills tested at 2 to 3 mg. Making the situation worse, we began to see the fentanyl mixed into heroin, again without the user knowing. In British Columbia, overdose deaths increased 11 per cent from 2013 to 2014. By the end of 2015, fentanyl wasn't just being added to heroin, it was replacing heroin, and deaths rates were about to accelerate.

On Christmas Eve, 2015, as I left police headquarters, I asked the night shift supervisor to call me if there were any overdoses overnight. He called soon after I got home, then again an hour later, and once more before midnight. We agreed he'd track the overdoses and call in the morning. That weekend, a record nine people died due to drug poisoning in Victoria, including the 22-yearold daughter of my colleague at the police department.

We read her text messages to the dealer, "I don't want any fentanyl, people are dropping like flies" she messaged, clearly concerned. "Don't worry, it's just H," replied the dealer. But of course, it was fentanyl, and it killed the young woman instantly.

In British Columbia, overdose deaths mounted rapidly; in 2015, on average, one person succumbed to fentanyl poisoning per day; by 2017, it was four per day. By that time, everyone who used drugs knew that fentanyl was saturating the market. And while some people tried to avoid it, others sought it out. One dealer I knew marketed his fentanyl supply as "kilz", attracting customers willing to take the risk, drawn to the extreme potency.

To stop the flow of fentanyl from China, in 2019, U.S. and Canadian authorities lobbied the Chinese Government to regulate fentanyl within its borders and take measures to prevent chemical companies from shipping it overseas. In response, crime groups based in North America pivoted away from importing fentanyl from China, and began to produce it in domestic laboratories. However, to make fentanyl they needed precursor chemicals, the essential ingredients, and in China these chemicals remained unregulated as many were used in legitimate industry as well as fentanyl production, their “dual-use” status made restricting their movement nearly impossible. Now crimes groups began transporting drums of chemicals, and the smuggling method transitioned from air cargo to marine shipping.

The Port of Vancouver proved to be particularly vulnerable. Each day, workers offload over 8,000 containers. The Canada Border Services Agency, tasked with intercepting these precursors, searches less than one per cent of the daily arrivals. Most containers enter Canada without inspection. Criminals move the precursors from the Port to clandestine laboratories operating in the vastness of rural Canada. The ports on Mexico's Pacific coast proved equally vulnerable, and precursor chemicals offloaded there ended up in fentanyl super labs, where cartel "cooks" produce thousands of kilograms per week; fentanyl that's smuggled across the southwest border where it's moved to hub cities like Houston and Los Angeles and then onward using a spider web of highways that take it across the continental U.S.

Back in British Columbia, it was alarming to learn that in 2023, cartel "cooks" from Mexico had travelled to Canada to share their expertise. Producers began making fentanyl that is more toxic, and in larger amounts; doses are ten times more toxic than fentanyl produced in China, and the kilogram price has dropped 90 per cent due to its widespread availability.

Countries that haven't yet experienced a saturation of fentanyl or a similarly deadly synthetic opioid should pay attention to the North American experience, where one drug has ravaged two countries for a decade. Between 2016 and 2024, fatal overdoses, mainly attributed to fentanyl, took the lives of almost 51,000 Canadians and at its peak, fentanyl killed over 100,000 Americans per year.

However, there are signs that fatalities peaked in 2022, though the reasons are still unclear, and the decline is not uniform; in British Columbia and California, overdose rates are falling, but in Alaska and Nevada, rates are still rising. Undoubtably fentanyl is here to stay, but this tells us that its impact, like that of other drugs, will rise and fall as law enforcement and governments respond.

Inspector Conor King is the officer in charge of the Investigative Services Division at VicPD, and is recognized internationally as a drug expert. With 28 years of policing experience and a career focused on investigating and disrupting the drug trade, he is regularly invited to speak and present on topics ranging from trafficking to decriminalization.

-30-